Note: This article is based on a session at the Associated General Contractors of America 2024 Surety Bonding and Construction Risk Management Conference. It was originally published by the AGC.

“If the only tool you have is a hammer, it is tempting to treat everything as if it were a nail.” – Abraham Maslow

Underlying this observation is, of course, an invitation to reach beyond our comfortable perspectives and to take a fresh look at the problems that we are trying to solve. While none of us would deny the wisdom of this ideal, in our busy practices it’s tempting to hammer away at the same old problems in the same old way. We hope this paper and our presentation can provide some new techniques and approaches to assist you in successfully resolving your mediations. Why settle for compromise when excellence is at hand.

I. Negotiation Paradigms and Styles

A central consideration when shaping your mediation is selecting the mediator that best suits your position in the controversy to be resolved. After considering subject matter expertise, the mediator’s approach to the negotiation becomes an essential element in your selection process. The risk when considering mediator styles is to oversimplify because an effective mediator will undoubtedly employ numerous approaches when attempting to facilitate a settlement among the parties. Nonetheless, understanding the paradigmatic approaches to interacting with the parties and framing problems will be instructive when identifying the best mediator to meet the particular challenges presented by your dispute.

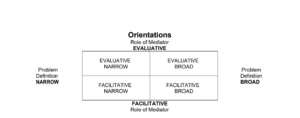

Law Professor Leonard L. Riskin developed a model to depict the basic approaches to the mediation process that is referred to as Riskin’s Grid. The grid is formed at the intersection of the continuum addressing the role of the mediator (ranging from evaluative to facilitative) and the continuum addressing the mediator’s definition of the problem (ranging from a narrow position based approach to a broad interest-based approach). While Riskin’s more recent scholarship suggests alternative grids to deal with more nuanced considerations, the basic model is a worthwhile reference when determining which mediator orientation is best suited to resolve your dispute.2

1 Leonard L. Riskin, Who Decides What? Rethinking the Grid of Mediator Orientations, Dispute Resolution Magazine,

Winter 2003 at 22 – 25.

2 Id.

A. Evaluative v. Facilitative Orientations

The evaluative approach has also been referred to as directive.3 An evaluative mediator is commonly seen as the “head banging” type that will push the parties toward resolution. Typical of this approach, over the course of the negotiations the mediator will likely inject his or her own assessment of the strengths and weaknesses of the issues being addressed and may even predict outcomes. To some, the influence exerted by an “evaluative” mediator stands at odds with the principle of party self- determination undergirding the mediation process.4 You should expect the evaluative mediator to be very influential in the process and its outcome. When weighing the suitability of this approach in your mediation, you should consider whether your position can withstand the scrutiny of the mediator and whether your negotiation team is equipped to handle that type of pressure. Remember, the mediator always represents the settlement and not your interests.

By contrast, facilitative or elicitive mediators seek to advance the process by helping the parties to make their own evaluations of proposals and assessment of risks.5 The parties are assisted by a mediator ready to ask each party probing questions, but reluctant to provide his or her own assessments. A facilitative mediator will allow the parties greater self-determination while serving as a learned guide throughout the process. When deciding whether a facilitative mediator is the correct fit for your dispute, critical thought should be given to how increased party influence may affect the likelihood of reaching an acceptable negotiated result. This analysis will turn heavily on your assessment of the business acumen and ethos of the negotiating teams, both the parties and the lawyers, participating in the process. A facilitative mediator probably is not appropriate if you believe any participant is likely to be uninformed of its exposure, inflexible in its evaluation, or may attempt to seize the moment by steamrolling all the participants, including the mediator, with an errant view of the controversy. Conversely, an evaluative approach is more conducive to a circumstance with an opponent who is likely to perform a reasoned case assessment and negotiate on that basis.

3 Id.

4 Id.

5 Id.

An often-overlooked consideration when selecting a mediator is the mediator’s own view of his or her role in the process. Does the mediator believe that his or her essential purpose is to obtain a settlement? If so, be prepared to have some pressure applied if the opposing participant remains unyielding. Alternatively, is the mediator’s aim to support sound decision making, first and foremost, leaving the settlement as the parties’ responsibility? When weighing these differing tendencies, consideration should include how the parties involved in your mediation (including your own negotiating team) are likely to respond to pressure to compromise or having greater autonomy in the process.

B. Narrow Problem Orientation v. Broad Problem Orientation

An important factor that influences a mediator’s orientation is their definition of the problem. In Riskin’s Grid, the question of problem definition is presented by establishing a continuum ranging from narrow to broad.6 A narrow conception of the problem begets a process that proceeds “in the shadow of the law” with the parties’ legal rights central to the debate. At the other end of the spectrum, a broad definition of the problem plumbs the parties’ interests beyond the legal question presented by the immediate circumstance. The parties are viewed against the wider vista of their relationship to each other and the marketplace or community within which they

participate. Care should be taken when framing your mediation as to which view of your dispute would promote the best resolution. Dispute resolution theory contrasts two bargaining models which characterize a mediator’s problem orientation. The most familiar of these approaches is referred to as distributive or competitive bargaining. As the name suggests, this process involves each party seeking an advantage by maintaining a position that allows it to obtain an outcome that reflects a favorable number along a continuum of competing demands. The opposing model is integrative or cooperative bargaining in which the possibility of a negotiated solution is sought beyond the parties’ opposing positions on a particular issue. The dispute is recast against the broader context of the parties’ interests, with less immediate emphasis placed upon the parties’ differences. As most negotiations will involve elements of each of these bargaining methods, it is important to appreciate the subtleties of each.

1. Distributive (“Competitive”) Bargaining

In a distributive negotiation, the parties distribute between or among themselves the value being negotiated. In the context of commercial litigation, a distributive negotiation is often conducted concerning a monetary sum associated with the parties’ respective responsibility for a particular legal problem. Distributive bargaining is characterized by competitive maneuvering to obtain the

most advantageous position allowable with respect to the relatively fixed subject of their competing monetary demands. Inherent in the distributive bargaining process is a tension between the competition generated by the “zero-sum” exchange and the desire to cooperate in reaching a consensual solution of the problem. A successful negotiator recognizes the tension between competition and cooperation and manages it by being mindful of the dynamics of distributive bargaining and the disposition of the participants in the negotiation.

6 Id.

There are a few operative principles that all negotiators must be aware of when engaged in distributive bargaining. The primary principle is that the matter tends to settle at the midpoint between the first two reasonable offers. Given this dynamic, it stands to reason that opening offers are critical in establishing the settlement bracket. A solid opening offer or “anchoring position” can go a long way toward determining the success of the ensuing negotiations. The best opening offer will be seen as credible, but without conceding more than is necessary to motivate the other party into making a credible counteroffer. Equally important is the ability to choreograph the exchange of concessions leading toward the final settlement amount. How to precisely plan your moves depends, in large measure, on the parties involved in the negotiation. Yet, there are certain negotiating norms that should inform your thought process. As an initial matter, always remember that the parties expect to exchange several offers. Any effort to circumvent the anticipated bargaining process by making a “fair” offer early will be interpreted as another step in the process and an opportunity to seize additional

concessions. Further informing the pace of the negotiations, unless there is a specific deadline, the time taken between concessions increases as more concessions are made and the size of each successive concession becomes smaller. Professor Peter Robinson of the Straus Institute for Dispute Resolution was particularly engaging on this point by explaining to prospective mediators that there are expected steps in this dance and that failing to honor them only causes a party to step on its own toes. Rather than being put off by a process conceived by some as antagonistic and coarse, he encouraged his students to revel in the sound of the “mariachi music” as the steps of the dance unfold.

2. Integrative (“Cooperative”) Bargaining

The concept underlying integrative or cooperative bargaining is to assist the parties in viewing their dispute in a broader context. Consideration is given to the parties’ interests beyond the resolution of the issue(s) presented by their present dispute. Understanding each party’s broader interests presents an opportunity to satisfy the other’s needs without necessarily making a solution is no longer a zero-sum game. Instead of a competition pitting the parties in a battle over a defined value the focus is expanded by inviting the parties to consider alternative ways they can create value for each other without necessarily losing in that exchange. In theory, the competition animating distributive bargaining is replaced by a more cooperative model where the parties can increase the possible benefits to be shared, while also increasing the likelihood of reaching a negotiated settlement. The integrative bargaining process begins with an effort to create a list of the interests underlying each party’s negotiating stance on the defined issues. The mediator also accounts for the parties’ overarching needs as presented by the commercial circumstance. A skilled mediator is invaluable at identifying interests that lie below the surface of the dispute. Dispute resolution theory refers to these interests as the “below the line” interests. Fertile areas to examine include the value the parties ascribe to: (1) their relationship; (2) their standing in the industry or business community; and (3) the principles at issue in the dispute to be decided. After defining each party’s interests in a negotiated solution, the varying means of satisfying these needs are explored during discussions with the parties. The benefits of integrative bargaining are most readily realized when the parties value an ongoing relationship. Relatedly, the success of an integrative approach relies on capturing or developing trust between the negotiating parties. Attempts at innovation almost always rest on the ability of the parties to trust each other. For construction professionals, situations where maintaining an ongoing relationship is at a premium include: (1) disputes on an ongoing project; (2) disputes when the parties are performing two or more projects together; and (3) longstanding business relationships. Even if your project does not appear suited to an integrative bargaining approach, the potential for mining below-the-line interests should not be ignored because creative negotiators can oftentimes gain some advantage by utilizing interest based

considerations.

II. Psychological Insights to Assist in the Bargaining Process

As is the case with all negotiations, there are numerous psychological principles at work during a formal mediation session. Presented below are, in our experience, the most impactful psychological dynamics at play when mediating complex construction cases.

1. Defining a Successful Mediation Prior to engaging in any mediation, each participant should spend ample time evaluating its case

and outlining flexible goals for the proceeding. A primary consideration is defining what constitutes a successful mediation. Defining settlement as the goal can put a participant in a compromised position from the onset. A more beneficial approach is to plan on making a sound risk evaluation of any settlement opportunity informed by an accurate assessment of the case including the facts, legal risks, and the transactional and reputational costs.

2. Perception is Reality

Perception is reality is a psychological principle that governs much more than behavior during mediations. Nonetheless, this common way of interpreting our environment has an extremely important role in establishing the outcome of the mediated settlement. The only version of the truth the mediator and many key decision-makers will be exposed to is that advanced during the mediation proceedings. Mental impressions made from key exchanges of information during the proceedings will shape the reality of the dispute for the decision-makers determining the outcome of the mediation. This being the case, the importance of advancing a well-reasoned and factually supportable position at the mediation cannot be overstated.

3. Overcoming Inflated Case Assessments

The bias in favor of defending one’s stance presents a major obstacle in almost every mediation. This tendency is reinforced by the differential attention often paid to positive and negative facts in the case – with positive facts being accentuated and negative facts being explained away. An inflated case evaluation often results in an unproductive negotiation stance. With an overstated case assessment as the reference point, reasonable offers can be misperceived as unacceptable or, even worse, unproductive bargaining. This propensity to overvalue one’s case is particularly difficult to overcome when relevant decision-makers are not invested in the

mediation so that the parties’ case assessment may be changed. One way of combating this bias is to allow several opportunities for the exchange of ideas as part of the mediation process. In complex cases, this exchange of information may include written mediation statements, opening presentations and the submission of questions and answers during the caucus sessions. Finally, the parties can always request that a neutral case evaluation be offered as part of their mediation process.

4. The Transformative Power of Listening

Our innate desire to be treated fairly impacts the resolution of any dispute in which we are involved. As such, this need for fairness is at work in every mediation. The dispassionate case evaluation engaged in by the lawyers, as well as the calculated exchange of offers during the bargaining sessions, can undermine the perception of fairness in the mediation process. Skilled mediators can address the need for fairness by making certain that participants in the mediation are afforded the opportunity to be heard. Giving parties a chance to explain their actions and vent their frustrations can transform their experience of the entire mediation process. While a suggested compromise may seem unfair taken alone, the sense of fairness engendered in the mediation process by a mediator who is a good listener may be enough for the parties to reach an agreement.

5. Addressing the Need for Judgment

Beyond the need for a resolution, mediation participants are also often seeking a determination of right and wrong. Parties involved in a dispute hope to have their position vindicated as well as have their opponent’s position found wanting. The desire for judgment can become particularly difficult to overcome when the focus moves from conducting an appropriate risk evaluation to a declaration of right or wrong. An unchecked need to attribute fault results in anger and the associated need to retaliate, which shrinks the bargaining zone for potential resolution. In some cases, a mediator can blunt the effect of the need for judgment by recasting a party’s actions as the result of circumstances instead of malice or ill will. More often, however, the mediator will be forced to look toward decision-makers who were uninvolved in the circumstances giving rise to the dispute for a more dispassionate evaluation of the case.

6. Guarding Against Reactive Devaluation

A breakdown in trust is often what leads parties to require a mediator. Sometimes, the parties’ tattered relationship prevents one or both participants from properly appreciating offers exchanged. The practice of discounting the offers or suggestions of the other party involved in a dispute simply because it originated with them is referred to as reactive devaluation. Simply put, this is the nagging suspicion that no matter what the other side has suggested must be either untrue or a trap because they offered it. On occasion, a mediator can combat this problem through the exchange of information supporting the value of the proposition of offer.

III. Closing Techniques

A mediator’s skills are differentiated from the ordinary when the parties’ negotiations reach an impasse. As the day grows long, and tensions rise, a mediator’s ability to instill hope, supply energy and present new approaches, is essential. Indeed, it is at the point of impasse, when the credibility established by the mediator throughout the process needs to be leveraged into results. Set forth below are some oft used mediator techniques for jump starting negotiations that have stalled.

A. The “Parade of Horribles” – Revisiting the Litigation Risks

One of the essential benefits of a mediated agreement is that the parties retain control over the outcome. Suffice it to say, this element of party control is ceded to others when a case is submitted to litigation or arbitration. While this concept is usually presented by the mediator in the convening or opening stages of the mediation, the value of party self-determination and the attendant risks in trying the cause are often lost in the tussle of competitive bargaining. At the point of impasse, the parties are toeing up to the edge of the “litigation cliff” and it is the mediator’s job to remind them of the risk of jumping. This is the point in the mediation where a stark review of the litigation risks will be most instructive. This process often includes a discussion of a party’s BATNA. In mediation, the best alternative to a negotiated agreement (BATNA) refers to the course of action that a party will have to pursue if they are unable to reach

a mutually acceptable agreement through mediation. In other words, if the parties are unable to reach a settlement, the BATNA represents the party’s next-best option. BATNA is not necessarily a preferred outcome, but rather a realistic alternative to consider.

For instance, if the parties are unable to reach a settlement through mediation, they may pursue other forms of alternative dispute resolution (ADR) such as arbitration. This may be a viable option if the parties believe that a different form of ADR will yield a better outcome when resolving the dispute. At times, the BATNA may be going to trial if one party believes that it has a strong case and that a judge or jury is likely to rule in their favor. Professor Jim Craven of the Straus Institute, refers to this review of the litigation risks as the

“Parade of Horribles.” A review of the risks of litigation can include: (1) the uncertainty of the result; (2) a review of the legal and expert costs; (3) a discussion of the lost opportunity cost associated with management’s involvement in a time consuming and emotionally draining dispute; and (4) the reputation costs associated with the litigation itself and a possible adverse outcome. Professor Craven offers an interesting variant on this approach whereby he encourages the parties to visualize life without the emotional torque of the pending dispute. Anyone familiar with the risk and emotional strain high stakes construction litigation puts on the parties will immediately appreciate the power of this approach.

B. A Mediator’s Proposal or Case Assessment

A powerful tool in the mediator’s arsenal is the mediator’s proposal or case assessment. As with many of the techniques discussed herein, there are numerous ways this approach can be implemented. A mediator utilizing this technique can go as far as proposing final settlement terms for the parties’ consideration. Other related options include a mediator’s assessment of a particular impasse issue or a mediator’s overall assessment of the likely outcome of the dispute if litigation is pursued. Dwight Golann, Nearing the Finish Line: Dealing with Impasse in Commercial Mediation, Dispute Resolution Magazine, Winter 2009 at 4. Use of this impasse breaker warrants particular consideration. An essential feature of the mediation process is party self-determination. A mediator, imbued with authority by virtue of his or her selection and role in the process, exerts substantial influence over the outcome of the negotiations when making a proposal. Accordingly, the parties’ desire to have the mediator provide a proposal or case evaluation in the event of an impasse should be considered during the convening or opening stages of the mediation. Understanding whether a mediator’s proposal or case assessment may be forthcoming can influence a party’s decisions throughout the process, including the disclosure of confidential information.

C. Other Techniques When All Else Fails

1. Narrow the Gap by Proposing Linked Moves

Parties are often reluctant to move toward their bottom-line position out of a concern that a further concession will be interpreted as a lack of resolve and thus, will fail to garner a corresponding move from their negotiating partner. In this circumstance, the mediator can bridge the gap by proposing linked moves. While there are many variations of this technique, the purpose is to gain further concessions from each party by establishing the value of the corresponding moves. When effective, a new narrower gap is established as the basis for further bargaining.9 This mediator strategy is often implemented through the use of hypothetical questions posed to the parties in their separate caucus rooms. “What if” questions are used to obtain a commitment, that should a certain offer be forthcoming, an agreed upon simultaneous move would then be made.10

2. Restructuring the Mediation

The dynamics at work in a caucus room during a protracted mediation session vary based on the differing personalities comprising the negotiating team. Having spent a good deal of time locked away in caucus rooms as a party advocate, I can attest to one constant – emotional strain. The mediation process forces parties to uncomfortably relive their dispute. The rigors of distributive bargaining can further fracture already broken relationships. Moreover, the anxiety and emotion expended in the bargaining effort exhausts many participants. A skilled mediator studies the interactions throughout the mediation process. The mediator will be examining both the exchanges between the parties and the interaction among the members of the separate negotiating teams. As the process unfolds, the mediator develops impressions as to which participants are advancing the possibility of reaching an agreement and which individuals are detrimental to the process. At the point of impasse, the mediator can restructure the mediation to refresh and reinvigorate a process that has ground to a halt. 8 Dwight Golann, Nearing the Finish Line: Dealing with Impasse in Commercial Mediation, Dispute Resolution Magazine, Winter 2009 at 4 – 10.

9 Id.

10 Id.

There are many options a mediator has when restructuring the process to mine fresh perspectives and create new opportunities for a breakthrough.11 Options for restructuring the process include: (1) adding participants to, or subtracting participants from, the process; (2) having the key decision makers from each side meet together without their respective negotiating teams; (3) inviting the opposing lawyers and/or experts to meet apart from their clients; and (4) convening a new joint session to address a narrow point of contention.12

IV. Conclusion

Don’t settle for unprincipled compromise. We trust that the principles discussed in this paper will prepare you to maximize the value of any negotiated settlement or to assess the value of your cause so you know when it’s time to walk away.

11 Id.

12 Id